Rosso’s uniqueness and importance in the history of sculpture is established by his having approached his medium as a way of seeing, feeling, and creating images that reject what to that point had been the concept of sculpture as solid and static. As Rosso said: “It is all a question of light. There is no matter in space.”

The Italian artist Medardo Rosso (1858–1928) was instrumental in expanding the definition of sculpture for the modern era. Not only did he focus on everyday, contemporary subjects, but he also experimented with light in order to render sculpture ephemeral and seemingly insubstantial.

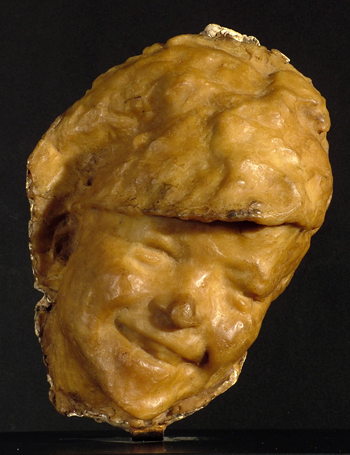

Birichino by Medardo Rosso

His heads and figures—frequently portrayed as tired, meditative, laughing, or melancholy—appear to be caught in fugitive visual, physical, or emotional states. As fleeting “impressions” of modern life, they stand in marked contrast to the monumental, idealized depictions typical of traditional sculpture before and during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

TECHNIQUE:

His technique was truly astonishing for the 1800s. Sharon Hecker writes in a catalog essay, “Rosso became the only artist of his time to publicly locate the creative moment of sculpture in the art of casting.” Whereas most sculptors conformed to the traditional practice of consigning their clay or wax or plaster “originals” to a professional foundry to be cast in bronze, Rosso turned the casting process into something akin to a performance art. “He did so,” writes Ms. Hecker, “in his Paris studio in front of select groups of writers, poets, artists, critics and potential clients … in a private mini foundry he had built directly into his Montmartre atelier.”

Paris at Night by Medardo Rosso

The “unfinished” quality of his bronze and wax over plaster figures can be thought of as following the esthetic of a sketch-like effect in which the figure is caught in the process of evolution.

Laughing Woman by Medardo Rosso

This is related to the “non finito” of many of Michelangelo’s sculptures. One has the awareness of an image coalescing out of Rosso’s manipulatable, translucent wax. Eugene Carriere’s (1849-1906) monochromatic brown paintings, in which his figures emerge out of a dense atmospheric fog as if they are visions produced in a trance, come to mind. This striving for the essence of a spiritual or emotional reality would ally Rosso to the Symbolist movement emerging in the mid-1880s. In cases where more than one duplicate was made, in each wax-over-plaster he varied the details by allowing the working of the wax to direct the creative process rather than simply replicating earlier versions of the same sculpture.

RODIN & ROSSO

More important to Rosso’s career, however, are the three versions of an adult male figure called, “Bookmaker” (circa 1894), for this was the sculpture that caught the attention of Auguste Rodin, who openly acknowledged its influence in the creation of his own more monumental Balzac (1891), one of the crowning achievements of his later years.

Bookmaker by Medardo Rosso

Rodin was, in any case, a huge problem for Rosso. Both as a sculptor and a public personality, Rodin was so overwhelming that his command of the scene had the effect of relegating the work of his contemporaries to a marginal status. Understandably, Rosso was somewhat paranoid on the subject of Rodin; he came to believe that Rodin had “stolen” something from him in the creation of his Balzac.

As Hilton Kramer wrote, “If, in the end, we are left with the impression that Rosso’s oeuvre remains in some sense incomplete, that too may account for the fugitive course of his reputation: He left it to the many sculptors he influenced to carry his ideas to completion.”